Project:Turing Machine: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

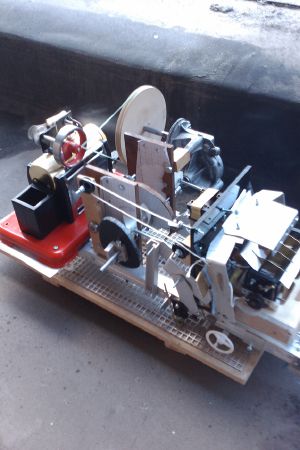

[[ | [[Image:SteamRun1.jpeg|thumb|left|alt=Picture of the Turing machine in December 2010|Test run with a steam engine]] | ||

During 2010/2011, [[User:Srimech|JimM]] built a mechanical Turing machine out of scrap parts with just a few custom 3d-printed parts. I demonstrated it at Newcastle Maker Faire in 2011, when it was working, just, but unreliably. I'm currently trying to make a second version mainly from laser-cut acrylic which should be prettier and more reliable. | |||

For background, you might want to read the XKCD strip [http://xkcd.com/505/ A bunch of rocks]. The scheme mentioned in this strip is Wolfram's rule 110 cellular automaton, which this machine emulates. This should also give you a good idea of how quickly this machine will operate. | |||

A video of it operating at Maker Faire 2011 is here: http://www.youtube.com/embed/40DkJ9vt5CI | |||

=== Design === | |||

The machine is a 5-symbol, 2-state universal Turing machine based on the 5x2 theoretical machine shown to be universal by Wolfram. This was until recently the simplest Turing machine known to be universal. It has since been surpassed by a 3-symbol, 2-state Turing machine, but the extra symbols do not make the mechanical design significantly more complicated. | |||

Data is stored in the positions of ball bearings on a square metal grid. The machine picks up a ball bearing from one row, moves it to (potentially) different position on that row, then moves forwards or backwards one row. The machine also has 1 bit of internal memory. Ball bearings are lifted up from the grid by magnets, then drop into one of five channels. The internal state then diverts each channel into another two, giving ten possible channels. Each of these has levers in it which will alter the state of the machine or change the direction of the whole machine. The ten channels then map back to the five possible new symbols; this mapping is done by the 'maze' of channels near the base of the machine. | |||

Three cams in the middle of the machine control all the action. One pushes down a rod which will propel the machine forward or backward like a punt. The second pulls a cord which raises ball bearings to the top of the machine. The third resets the direction each cycle such that a very light movement can switch it between backward and forward. | |||

The whole machine is driven using a worm gear taken from a car windscreen wiper motor. The input shaft to this has a large pulley which can be driven by a small electric motor or a steam engine. | |||

=== Speed === | |||

The Turing machine operates at 0.02 Hz and needs a large number of cycles to do what a modern computer would do in one cycle. The following rule 110 pattern can perform basic arithmetic, showing the result of 3-2. | |||

00010011010011011111011111000100110111110001001101111100011111010111001101111100010011011111 | |||

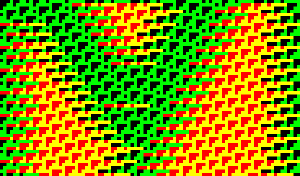

[[Image:rule110-3-2.png|thumb|left|alt=2-3 in Rule 110|Test arithmetic pattern]] | |||

Generations of the above pattern are shown left. This image shows about 5000 pixels, which would take this machine about 70 hours to compute. | |||

To do a general-purpose operation similar to a single instruction on a modern computer would, I would guess, take about 1 month. This makes it about 10<sup>16</sup> times slower than a modern CPU. | |||

[[Category:Projects]] | |||

Latest revision as of 00:59, 29 May 2013

During 2010/2011, JimM built a mechanical Turing machine out of scrap parts with just a few custom 3d-printed parts. I demonstrated it at Newcastle Maker Faire in 2011, when it was working, just, but unreliably. I'm currently trying to make a second version mainly from laser-cut acrylic which should be prettier and more reliable.

For background, you might want to read the XKCD strip A bunch of rocks. The scheme mentioned in this strip is Wolfram's rule 110 cellular automaton, which this machine emulates. This should also give you a good idea of how quickly this machine will operate.

A video of it operating at Maker Faire 2011 is here: http://www.youtube.com/embed/40DkJ9vt5CI

Design

The machine is a 5-symbol, 2-state universal Turing machine based on the 5x2 theoretical machine shown to be universal by Wolfram. This was until recently the simplest Turing machine known to be universal. It has since been surpassed by a 3-symbol, 2-state Turing machine, but the extra symbols do not make the mechanical design significantly more complicated.

Data is stored in the positions of ball bearings on a square metal grid. The machine picks up a ball bearing from one row, moves it to (potentially) different position on that row, then moves forwards or backwards one row. The machine also has 1 bit of internal memory. Ball bearings are lifted up from the grid by magnets, then drop into one of five channels. The internal state then diverts each channel into another two, giving ten possible channels. Each of these has levers in it which will alter the state of the machine or change the direction of the whole machine. The ten channels then map back to the five possible new symbols; this mapping is done by the 'maze' of channels near the base of the machine.

Three cams in the middle of the machine control all the action. One pushes down a rod which will propel the machine forward or backward like a punt. The second pulls a cord which raises ball bearings to the top of the machine. The third resets the direction each cycle such that a very light movement can switch it between backward and forward.

The whole machine is driven using a worm gear taken from a car windscreen wiper motor. The input shaft to this has a large pulley which can be driven by a small electric motor or a steam engine.

Speed

The Turing machine operates at 0.02 Hz and needs a large number of cycles to do what a modern computer would do in one cycle. The following rule 110 pattern can perform basic arithmetic, showing the result of 3-2.

00010011010011011111011111000100110111110001001101111100011111010111001101111100010011011111

Generations of the above pattern are shown left. This image shows about 5000 pixels, which would take this machine about 70 hours to compute.

To do a general-purpose operation similar to a single instruction on a modern computer would, I would guess, take about 1 month. This makes it about 1016 times slower than a modern CPU.